...

The Jameson Raid is a reminder of where that logic leads, and reflects the reckless adventurism we see in the CIP today, the betrayal of constitutional norms, and ultimately a deepening of divisions rather than their resolution.

...

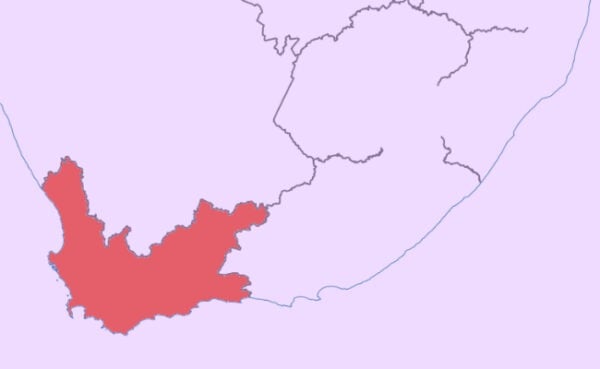

In South Africa, the line between opposition politics and secessionist fantasy began to blur when parties like the Cape Independence Party (CIP) started advocating the independence of the province, through legal and constitutional means.

The CIP traces its roots back to the early 2000s, when a handful of right-leaning activists in the Western Cape began to argue that the province’s distinct demographics, higher service delivery standards and political divergence from the African National Congress (ANC) justified outright secession.

Its leaders have included Jack Miller, a businessman and perennial political outsider, who has become the face of the party’s electoral forays. Miller and his colleagues have consistently argued that Cape independence – or “Capexit”, as supporters call it – would liberate the province from national misrule, high crime (never mind that Cape Town is the most violent city in Africa outside war zone areas) and economic stagnation. They cite Western Cape opinion polls suggesting support for greater autonomy, though actual votes for the CIP have remained negligible in local, provincial and national elections.

The party’s ideological make-up is eclectic. It mixes strands of Afrikaner separatism, conservative liberalism and, more recently, attempts to appeal to disillusioned coloured and English-speaking voters who are frustrated with ANC corruption. At the core of the party lies the impulse to convert the Western Cape into a sovereign state, whether through negotiated secession, a referendum or, more vaguely, a gradual erosion of national authority. This secessionist mentality is seen by most South Africans, especially black people, as treasonous.

Despite its marginal electoral presence, the CIP has exerted an oversized influence on South Africa’s political conversation. By aligning with civic groups like the Cape Independence Advocacy Group (CIAG) and leveraging social media, it has helped normalise the once-fringe idea of Cape secession, pulling even mainstream party supporters of the likes of Freedom Front Plus (FF+) and the Democratic Alliance (DA) into debates about “devolution” and provincial self-determination.

The DA, South Africa’s main opposition party, has recently intensified its campaign to devolve more powers from the national government to the Western Cape province. The latest demand is for control over the appointment of provincial police commissioners. On the face of it, the DA insists this is about efficiency – reducing crime, tailoring law enforcement to local needs, and countering what it calls the failures of the ANC. But beneath the rhetoric lies a more dangerous idea, an attempt to federalise a unitary republic through the back door.

The South African Constitution is clear. It establishes a unitary state, not a federation. Provinces enjoy certain powers, but the police, the army and foreign affairs remain under national authority for good reason. These institutions are the connective tissue of the republic, ensuring that no province, however discontented, can drift into quasi-independence. When the DA seeks to arrogate policing powers, or floats ideas about devolving immigration or railway control, it is not merely advocating “better governance”. It is nudging South Africa toward a patchwork of competing jurisdictions – a model the Constitution explicitly rejects.

Calls for a referendum on provincial autonomy, wrapped in the language of “self-determination”, are eerily reminiscent of the independence referendums that have fractured nations elsewhere. The irony is that South Africans do not need to look far into the history books to see the dangers. From the Balkans to Catalonia, referendums held under the guise of “self-rule” have unleashed centrifugal forces that tore apart states, inflamed ethnic divisions and left societies more fragile than before. Once the principle of provincial self-determination is normalised, the question is no longer whether secession happens, but when – and under what conditions of conflict.

If the dangers of this model are not yet clear, look at what is happening in the United States, a country with centuries of federalism behind it. There, Donald Trump’s kakistocracy has weaponised state powers against the union itself. Republican-led states now use their police and militia forces not to strengthen the collective security of the country, but to punish political opponents and intimidate protesters against Trump across state lines. Governors sue the federal government not merely on matters of constitutional principle, but to undercut national policy out of sheer partisanship. The result is a patchwork republic, where law and rights depend less on citizenship than on ZIP code.

South Africa, by design, chose a different path. The 1996 Constitution is a unitary pact: one republic, indivisible, where provinces may manage certain areas of competency, but the hard instruments of sovereignty – security, justice, international relations and others – belong to the nation as a whole. To flirt with referendums on autonomy in the Western Cape is to import things like America’s constitutional dysfunction without its historical scaffolding. It is to trade the hard-earned unity of a democratic South Africa for the illusion of local control, an illusion that will shatter the moment national cohesion is tested.

The Western Cape is a unique province. It is the one with the oldest imprint of not being governed by the ANC. It has nurtured this political identity apart from the rest of the country. Crime, unemployment and service delivery failures are real problems within the Western Cape also, but the DA, more than any other party, is good at marketing itself as the place of best service delivery – something people from its townships and rural peripheries often find fresh, but also profoundly dishonest. The daily realities of gang violence on the Cape Flats, inadequate housing in informal settlements, and the persistence of farmworker poverty make a mockery of the DA’s carefully cultivated image of “good governance”.

This sense of being different, of existing slightly apart from the rest of South Africa, is not new in the Cape. It is written deep into the history of the Cape Colony itself. Under Cecil John Rhodes’s premiership in the 1890s, the Cape’s economy was increasingly yoked to imperial designs, rather than to any collective South African destiny. Rhodes’s Cape government, and the mining capital that backed him, fostered the illusion that the Cape could chart its own path, insulated from the struggles of the Boer republics in the north or the African societies dispossessed all around it. That illusion reached its most cynical expression in the infamous Jameson Raid of 1895-6, a botched coup launched from the Cape against the Boer Republic of the Transvaal. It was an act of hubris, premised on the belief that Cape capital and British guns could reshape the region’s politics at will. Instead, it collapsed into a scandal, exposing both the arrogance of Cape exceptionalism and its fundamental instability.

Today’s rhetoric of Western Cape autonomy echoes those same fault lines. Then, as now, the Cape was tempted to see itself as separate, a kind of “better governed” enclave, with a political destiny detached from the rest of the country. The Jameson Raid is a reminder of where that logic leads, and reflects the reckless adventurism we see in the CIP today, the betrayal of constitutional norms, and ultimately a deepening of divisions rather than their resolution. When the DA markets the Western Cape as uniquely competent and uniquely deserving of autonomy, it is tapping into a colonial inheritance with a long shadow, a history in which the illusion of separateness has always come at great cost to South Africa as a whole.

South Africans know their history well. Apartheid itself was built on the fiction of “separate development”, a pseudo-federalism designed to weaken the black majority’s claim to a unified nation. The genius of the 1996 Constitution was that it rejected that fragmentation, binding the country together under a common Bill of Rights, common institutions and a common destiny.

I don’t think the DA is plotting secession – not yet, at least. But its piecemeal strategy to hollow out national authority through devolution risks the same endpoint. Federalism may work in places like Germany, but South Africa’s compact – painfully negotiated after centuries of dispossession – rests on unity. A Western Cape police force, answerable only to a provincial premier, would not be a modest reform. It would be a breach in the wall of constitutional order.

By the way, the South African Constitution already recognises that policing is not purely a national matter. Provincial governments are not powerless bystanders. Section 206 of the Constitution explicitly provides that a province has the right to monitor police conduct, oversee the effectiveness of visible policing, promote community-police relations and even make recommendations to the national Minister of Police. The provincial premier may request the appointment or removal of a provincial commissioner, and while the final decision rests with the national executive, that decision must be taken in consultation with the provincial government. In other words, provincial commissioners are not unaccountable figures dispatched from Pretoria; they operate within a framework of dual responsibility, answerable both upward to the national ministry and horizontally to the province in which they serve.

This accountability is not theoretical. It has played out repeatedly in the Western Cape, where premiers and provincial community safety ministers have clashed with national police leadership. In 2012, Premier Helen Zille publicly accused the national police minister of failing to tackle gang violence in the Cape Flats and demanded greater provincial input into anti-gang operations. More recently, in 2018 and 2019, Premier Alan Winde pressed the national government for the removal of the provincial commissioner, citing the province’s constitutional right to intervene when policing was ineffective. Even the deployment of the army to gang-ridden communities in 2019 followed sustained pressure from the Western Cape provincial government on the national minister.

These episodes demonstrate that provincial leaders already wield significant influence over policing, and that provincial commissioners are indeed accountable to them in practice. The framework is one of shared responsibility, designed by the drafters of the Constitution to preserve the unity of the republic while still allowing provinces to shape law enforcement according to local conditions. The challenge is not the absence of provincial power, but the political will and administrative capacity to use the authority that already exists.

The DA’s frustrations with the ANC are understandable; so are the Western Cape’s citizens’ grievances with crime and governance. But the remedy cannot be the slow dismantling of the very republic that holds us together. South Africa’s future depends on building stronger national institutions, not carving out provincial fiefdoms.

The Western Cape is not a country. It is part of South Africa, indivisible and privileged because of our past. To pretend otherwise is not only unconstitutional, but perilous.

See also:

Reguit met Robinson: ’n Zoom-gesprek met Heindrich Wyngaard en Phil Craig